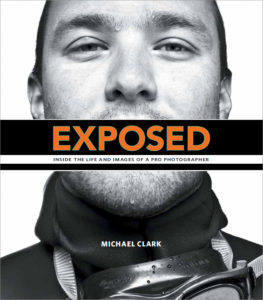

While revamping my website recently it was decided to take down a few of the stories I had on my portfolio website to simplify it a bit. I wanted to repost this insight into the life of a pro photographer here on the blog, and just now have finally gotten around to doing so. This is the first chapter from my book Exposed: Inside the Life and Images of a Pro Photographer (cover shown at left). Originally written in 2001 and entitled “Reality Check,” this article was updated in 2010 and then against was updated for Exposed in 2012. If you would like more information on Exposed and my other books please visit the Books section of my website.

While revamping my website recently it was decided to take down a few of the stories I had on my portfolio website to simplify it a bit. I wanted to repost this insight into the life of a pro photographer here on the blog, and just now have finally gotten around to doing so. This is the first chapter from my book Exposed: Inside the Life and Images of a Pro Photographer (cover shown at left). Originally written in 2001 and entitled “Reality Check,” this article was updated in 2010 and then against was updated for Exposed in 2012. If you would like more information on Exposed and my other books please visit the Books section of my website.

Control is a myth. I realized that five days into a three-day assignment in Joshua Tree National Park. The soggy walls of my mountaineering tent didn’t bode well for a rosy-fingered dawn. I’d been up at 5 a.m. for five days straight trying to get first light on a particular landscape. It had been raining sideways all five days, and I had yet to shoot more than a dozen images.

The campground was empty save for my friends Kurt and Elaina Smith, both of whom are phenomenal rock climbers. I spent five days hiking around in the rain checking angles and the setup for hundreds of different images. The best photo op I had was shooting inside Kurt and Elaina’s warm and cozy van, which doubles as their home. If not for the satellite TV and DVD player in their van, we would have gone berserk. Luckily, the morning of the sixth day dawned clear, and I was in position when first light hit the rock arch that I had been trying to photograph for six days. I spent the next few days shooting other images for the assignment and also some images of Kurt and Elaina rock climbing.

Fortunately, not every assignment is as laborious and frustrating as the one in Joshua Tree was. I am constantly amazed at how well many of my assignments go, especially considering that almost all of my work is shot outdoors. For much of my adventure sports work, the athletes need fairly specific conditions to perform at their best—or to even do what they do at all. Rock climbers generally don’t climb in the rain, downhill mountain bikers need calm weather to jump off huge cliffs, and likewise, BASE jumpers also need calm winds to jump. Time and time again when I’ve had big assignments the weather has cooperated, at least long enough for me to get what I needed.

My assignments can range from an afternoon near my office in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to weeks on end in remote corners of the world. I usually travel at least six or seven months a year. The rest of the time I am in the office talking with clients, pursuing work, editing and processing images, keeping up with the accounting, or sending out submissions and invoices to clients. There are no regular “hours.”

.jpg)

Above: The Opening spread of Chapter One in my book Exposed:Inside the Life and Images of a Pro Photographer

I started out shooting primarily rock climbing and mountaineering, and then I slowly branched out and started shooting all of the other adventure sports. With my background in adventure sports, clients have also called on me to shoot assignments that involve risky situations. For that reason, I’ve always included a workout as part of my workday when I’m back in the office so I can stay fit enough to get the shot while out in the field with world-class athletes. I don’t pretend be a world-class athlete, but I am in good enough shape to do what I need to do.

Almost always I’m carrying more equipment than the people I am with, and in most cases I need to be ahead of them to get the images I want. As an example, a normal day shooting rock climbers involves at the very least a 70- to 80-pound backpack. On big wall excursions, carrying up to 120 pounds is not uncommon, and by big wall I mean cliffs that are anywhere from 1000 to 4000 feet high—like El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. Shooting on big walls usually involves carrying loads of ropes and hardware up the backside of the cliff. Often, it takes more time to set up for a shot than it does to actually take it.

I tend to go very light (in terms of photography equipment) so the pack doesn’t get too heavy. Now, in the digital age, my main kit for just about any “adventurous” shoot is a Nikon D4 (or D810), three or four lenses, a small flash, and plenty of memory cards. My main kit includes three zooms: a 14–24mm f/2.8, the 24–70mm f/2.8, and a 70–200mm f/2.8. More often than not, I’ll bring a Nikon D810 as back up, especially in remote places and when I’m on assignment. With a closet full of camera bags, and depending on the shoot, I’ll choose the most appropriate camera bag(s) and pack the basic kit in it. When I’m shooting rock climbers, for instance, I take at most two or three lenses. If I am on a rope, I am usually fairly close to the climbers, so the Nikon 14–24mm f/2.8 wide-angle zoom and the Nikon 24–70mm f/2.8 medium-range zoom are my go-to lenses in that situation. Of course, depending on the sport I am shooting, I tailor my kit and how I carry it. For sports like surfing or whitewater kayaking, I might not carry as much gear while shooting, but often I have more equipment back in the car if needed. If I am using artificial lights, the amount of gear involved on a shoot can balloon to a few hundred pounds or more, and that usually requires an assistant (or two) just to get everything to the location and set up. Using large, battery-powered, studio strobes on location can certainly complicate a photo shoot, but it can also very easily set those images apart from anything else in the industry—and that is precisely the reason to use them.

For some situations, it isn’t about how much gear you take but how little you can get away with. When shooting in very remote locations, I trim down the kit to one body and one or two lenses depending on the sport. In the mountains I trim it down even more. The less gear I carry, the more it forces me to become creative. And I really prefer to be unencumbered when shooting. No matter how much gear I have with me, when I start shooting in earnest, I have only one camera around my neck. I’ll ditch the camera bag and come back to it if I need to. Having a camera bag hanging off me doesn’t allow me to move and explore the location like I do naturally with a single camera and lens.

No matter how much gear you have (or how little), shooting an assignment is hard and stressful work. You have to come back with “the shots,” and the shoot doesn’t always go as planned. Throw in the fact that I’m often working on ropes and hanging thousands of feet off the deck, and you start to get the picture, no pun intended. It can take a lot of time just to get into position, and sometimes I wonder if my success as an adventure photographer is directly related to my ability to coax athletes to get up early, warm up on their hardest projects, and to do it “one more time” over and over again.

Many of the athletes I work with have become close friends. To capture what they are experiencing, I must be there with them, and that isn’t always pleasant. Most of the time we are camping, and sometimes even simple amenities like a shower seem a world away. National Geographic’s photo editor, Kent Kobersteen, summed it up when he said, “The really strong photos come from those situations where the last thing you want to do is take pictures—when everything is going to hell, when the storms are raging and everyone is trying to hang on. Those are going to be the most telling images.”

I am also always aware of the sudden “courage” athletes gain when a camera is pointed at them. To date, I’ve not had anyone get seriously injured on a photo shoot, but there have been some very close calls. I’ve seen a kayaker under the water for 12 minutes, a mountain biker jump off a 40-foot cliff and crash hard, and rock climbers take serious risks. The kayaker survived because of his wise decisions and with the aid of his experienced companions. The mountain biker was scraped up a bit and his rear wheel exploded when he hit the ground, but amazingly, he was unhurt. And although I’ve seen a few really scary rock-climbing falls, some of which resulted in extensive injuries, I’ve never seen anyone permanently injured. Just as with my career, in the sports I photograph, everything is a risk—albeit a “calculated” risk.

The reality is that there is precious little I can control on most of my photo shoots aside from coordinating the action or modifying the light. In addition, freelance photographers might soon be a dying breed. The competition is fierce in this business, and corporations are always asking for more usage rights with no extra compensation. There is more competition in this industry than ever before, and photographers need to have a fair amount of business savvy as well as the ability to produce top-notch work.

On top of that, digital photography has revolutionized our industry, and photographers are taking on huge expenses they never had to deal with before. Digital has also brought with it a very steep learning curve, the opportunity to create images that were not possible before, and unprecedented control over the final image. And it is also making photography more exciting than it has been in a long time.

In the end, there is much more to working as a professional photographer than just capturing the images. Many photographers tend to make the work sound so glamorous. They leave out the unpleasantries like sleeping in airports, 90-hour workweeks, and the tough realities of owning your own business. In this era of ever-increasing expenses, dog-eat-dog competition, and shrinking assignment rates, you must work extremely hard and count perseverance as a good friend if you want to make it in this business. I would only recommend this profession to those obsessed with creating and sharing their images; to those who can’t imagine doing anything else.

Thanks for sharing.

I’m looking to upgrade from a D90.

It’s a “dog eat dog competition”.

BR